Service History

The

Frank O'Connor is a product of one of the most remarkable shipyards on the Great Lakes. Between 1870 and 1903, well after most major shipyards had made the inevitable transition to steel hulls, Captain James Davidson's yard in West Bay City, Michigan, stretched the limits of wooden boat technology, eventually making some of largest wooden ships on the Great Lakes and some of the longest ever intended for deep water navigation. (See, for example, the

Pretoria.)

Davidson's long preference for wooden hulls was due less to a reverence for tradition than to simple economics. Davidson's competitors faced huge capital outlays as they retooled their yards and retrained their workforces to build steel ships. Most, in fact, did not survive the transition. Davidson, however, spared himself the jolts of converting to steel. He exploited the supply of prime oak in the nearby Saginaw River area, stuck with his well-trained work force and well-equipped facilities, and pushed the art of wooden boat building to its limits. For many years, the strategy paid off. Davidson's inexpensive but efficient wooden boats continued earning him large profits until the Great Depression.

The

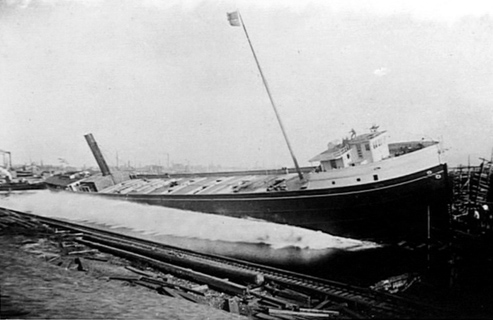

Frank O'Connor represents one of Davidson's many technological advances. Originally called the

City of Naples, it was built in 1892 with two sister ships, the

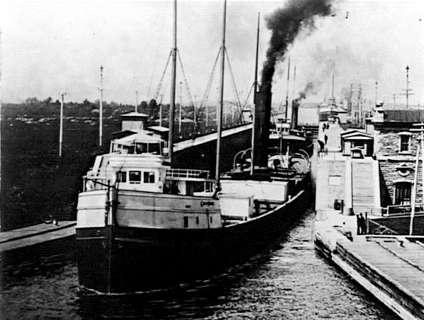

City of Venice and the City of Genoa. These three ships were the first of Davidson's 300-foot wooden bulk carriers. To reach these lengths, Davidson devised innovative ways to strengthen the hulls with iron and steel strapping. The

City of Naples measured 301 feet in length, 42 feet 6 inches in breadth, and 21 feet 3 inches in depth of hold. It had a gross tonnage of 2,109 and, as originally configured, could carry nearly 2,600 tons of coal or 100,000 bushels of grain. Despite their anachronistic building materials, the "Italian city" boats were driven by state-of-the-art, triple-expansion steam engine.

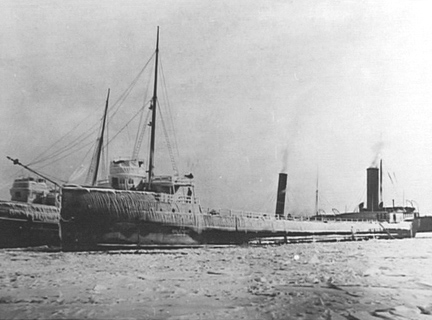

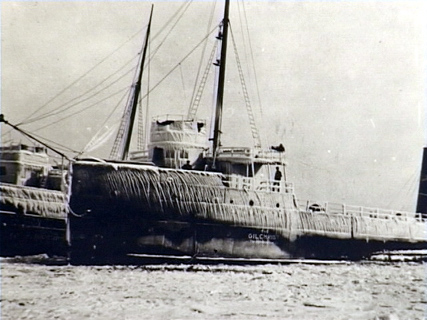

The

City of Naples operated in Davidson's fleet for about two years. It was then sold to J.C. Gilchrist of Cleveland, in whose service it spent 19 of its 27 years on the Great Lakes. A giant in the Great Lakes shipping industry, Gilchrist controlled the second-largest fleet on the lakes by 1905. The Gilchrist Transportation Company modified the

Naples by raising her approximately 18 inches, which increased her ore-carrying capacity by more than a third, to about 3,400 tons.

Commercial opportunities on the lakes began declining in 1906, and the Gilchrist Company found itself overextended. Cargoes were in short supply, and independent operators like Gilchrist were hit hard. Some ships did not "turn a wheel" for two years. Gilchrist's company suffered serious setbacks, compounded by Gilchrist's poor health, and eventually slid into receivership. In 1913 the

City of Naples was sold to Norris & Co. of Chicago. In 1914, she was picked up by the Tonawanda Iron and Steel Company of Tonawanda, New York, and given to the command of P.F. Powrie. However, the American economy was still sluggish, and Tonawanda had little use for an old wooden bulk carrier. The

Frank O'Connor saw no service that year.

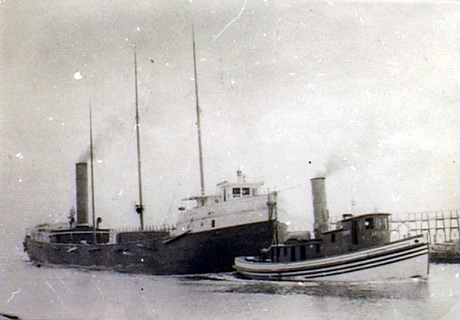

In 1916, perhaps anticipating the United States' entry into World War I and the coming wartime shipping boom, Tonawanda ship chandler James L. O'Connor ventured into the transportation business. He purchased the

Naples and renamed it after his son, Frank.

The

Frank O'Connor operated profitably during the war years, but wartime profits came at the expense of human lives. For the O'Connor Transportation Company, the cost included the death of young Frank O'Connor on a German battlefield on May 3, 1918. The young man's namesake met its own demise seventeen months later. On October 2, 1919, the

Frank O'Connor caught fire and sank off the coast of Door County.

Final Voyage

It was the fall of the 26th year since the

Frank O'Connor began working the lakes. The massive old workhorse had left Buffalo, New York, on September 29, 1919, loaded with 3,000 tons of coal and bound for Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Three days later she steamed through the Straits of Mackinac, intending to follow Lake Michigan's western shore down to Milwaukee. The boat made good time in the favorable weather, and the crew expected to make port ahead of schedule.

The

O'Connor was several miles off the east coast of Door County at 4:00 p.m. on October 3, 1919, when fire broke out in the bow. Captain William Hayes, James O'Connor's son-in-law, immediately ordered the helmsman to steer directly toward shore, ten miles away. Roughly an hour later, the steering gear burned away, leaving the ship helpless about two miles from Cana Island. Captain Hays ordered all hands to board the lifeboats. Fortunately, the billowing smoke had attracted the attention of Cana Island lighthouse keeper Oscar Knudson. With his assistant, Louis Pecon, Knusdon met the retreating crew with a power boat and took their lifeboats in tow. Some time later coast guardsmen picked up the tow and pulled it into Baileys Harbor. The

Frank O'Connor was seen burning well into the night and eventually sank in about sixty feet of water.

The cause of the fire remains unknown. The two most flammable areas in the bow, the oil room and paint locker, were housed in steel compartments. Suspicion centered on a discarded match or cigarette butt. The ship had been carrying grain all season, and the grain dust caked in the hold reportedly "burned like tinder." The United States Steamboat Inspectors at Milwaukee investigated the incident and, in a trial the following spring, declared Capt. Hayes blameless in the incident.

The 3,000-ton cargo of anthracite coal, valued at $30,000 in 1923, inspired several salvage attempts. When initial search efforts failed to locate the vessel, it was assumed to have sunk in deep water. The early searchers, however, had looked too far to the north. On June 29, 1923, the Door County Advocate reported that Charles Innes of North Bay and Chester Smith of Milwaukee had found the wreck of the

O'Connor. The men, using two gasoline launches and a 1,000-foot-long rope sweep, dragged the area off North Bay and quickly found the ship. In August and September of that year, the Marine Salvage and Wrecking Company of Milwaukee worked for five weeks using centrifugal pumps to suck coal off the wreck. Hampered by bad weather, they recovered only 700 tons, not enough to warrant further efforts. The wreckers also claimed that most of the coal had been lost when the sides of the ship burned away.

In 1935, Charles Innes, still believing that money could be made from the old steamer, interested the noted Chicago diver Frank Blair in another salvage attempt. Innes' son-in-law, Charles Rohrback, relocated the wreck after three weeks of dragging "about three miles off of the point in 65 feet of water." One hundred tons of coal were recovered from the site, and plans were made to return the following year with better equipment. The latter scheme never came to fruition, and the

O'Connor lay quietly forgotten until rediscovered by modern sports divers.

After intensive searching over the years, the rediscovery of the

Frank O'Connor was reported to the Wisconsin Historical Society in the fall of 1990. Its proximity to shore and moderate depth make the site accessible to sport divers and looters. Because of its archeological value and its vulnerability to thievery, the

Frank O'Connor became top priority for field survey in 1991.

Today

The wreck of the

Frank O'Connor lies in 65 feet of water, about 2.6 miles north-northeast of Cana Island (GPS : N 45° 6.866', W 87° 0.726'). The visibility ranges from 25 to 35 feet, and the water temperature varies from about 40° to 60° F during the summer.

The

Frank O'Connor is truly a transitional vessel. Representative of the terminal stages of large wooden bulk carrier construction, the

Frank O'Connor is equipped with modern steam engine machinery. The huge museum-quality triple-expansion steam engine and boilers sit on their beds and rise more than twenty feet off the bottom. The engine cylinders measure 20, 33, and 50 inches in diameter. They had a 42-inch stroke and turned the 12-foot diameter propeller, which is still attached, at 85 revolutions per minute. Steam was supplied by two Scotch boilers, 11 feet in diameter and 13 feet in length. The boilers had four furnaces, with 102 square feet of grate and 3,462 square feet of heating surface, which produced 160 pounds per square inch of steam pressure.

Off the stern, aft and lying to port of the propeller, the

Frank O'Connor's rudder has broken from the hull and lies flat on the bottom. From its head to its base, the rudder measures 27 feet 2 inches. The blade is constructed of five vertical timbers, with horizontal metal reinforcing straps and metal sheathing to protect against ice. The rudderstock is iron or steel, 17 inches in diameter.

Despite the fire and subsequent salvage operations, much of the lower hull of the

Frank O'Connor remains. The bilge is intact for the entire length of the vessel, but the existing portions of the sides have broken away, lying flat alongside the main portion of the wreck. The

Frank O'Connor's timbers and scantlings are of remarkable dimensions. The vessel's floors consist of triple-timbered frames, while the major longitudinals include a centerline keelson and multiple floor keelsons. The centerline keelson measures 20 inches by 20 inches, while the floor keelsons measure 12 inches by 12 inches.

The

Frank O'Connor's upper hull exhibits remnants of the iron cross bracing and steel or iron hogging straps that allowed Davidson to push his wooden ships beyond the 300-foot barrier. The heavy straps measure 30 inches wide by 3/4-inch thick. Due to the burning of the upper hull, many of these straps are displaced and lie strewn about both sides of the wreck.

The bow contains a great amount of artifactual material including chain from the chainlocker, a Trotman-pattern bower anchor with a pivoting arm, a mushroom anchor, the ship's steam windlass, a steam radiator, and remnants of the forward superstructure. The Trotman anchor measures 10 feet, 3 inches. This anchor remains shackled to its chain cable and sits among a great deal of chain in the chain locker. The mushroom anchor is still held inside the port hawsepipe and is clearly visible in historical photographs of the

Frank O'Connor. Such anchors were frequently used by bulk carriers of this period to aid in maneuvering a vessel's bow while it was moored or to keep a vessel properly oriented in a crosswind or current while awaiting entry into a lock, canal, or harbor.

The ship's windlass lies forward among the ruins of the chain locker. Originally positioned above on the forecastle deck, the fire dropped the windlass down onto the piled chain. It is a two-cylinder, steam-powered windlass. The cylinders are connected to an overhead crank that drives the windlass. Contemporary drawings show this worm gear also driving, via a bevel gear, a capstan situated on the forecastle deck above the windlass. As there is no donkey boiler to be found in the forward area, the windlass appears to have been powered by steam piped up from the main boilers.

The

Frank O'Connor is a valuable archeological and recreational resource. The ship appears to be unique in the Door County area as one of the few surviving historic steam vessels whose machinery is still largely intact and upright. It also represents the terminal period in wooden bulk carrier construction, and was a product of the noted James Davidson Bay City yard.

The

Frank O'Connor is owned by the state of Wisconsin and is managed by the Wisconsin Historical Society with assistance from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Like all historic shipwrecks in Wisconsin waters, the

O'Connor is protected under Wisconsin law as a state-owned archaeological site.

As with many other wrecks in the Great Lakes, zebra mussels have colonized the

Frank O'Connor. These prolific mollusks are very difficult to control, and further colonization appears inevitable.

Through the research conducted by the Wisconsin Historical Society, the

Frank O'Connor was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1994.

You can learn more about the

O'Connor's history and archeological findings in "Davidson's Goliaths: Underwater Archeological Investigations of the Steamer Frank O'Connor and the Schooner-Barge Pretoria," by David J. Cooper and John O. Jensen.

A dive guide for this vessel is available for purchase.

Confirmed Location

Confirmed Location

Unconfirmed location

Unconfirmed location