Service History

Built in 1916 by well-known Wilmington, Delaware, shipbuilders Harlan and Hollingsworth, the

Rosinco (U.S. #214160) was put to sea as

Georgiana III. The vessel would, in fact, change hands twice before becoming the

Rosinco. The other name was

Whitemarsh under the ownership of Commodore W.L. Baumin, 1919.

Wilmington had the distinction of being the "cradle" of iron shipbuilding, and Harlan and Hollingsworth became pioneer builders of iron and, later, steel ships in the United States. Indeed, competition in the region was intense. Noting similarities with the unsurpassed iron ship production along Scotland 's Clyde River in the latter nineteenth-century, maritime historian David Tyler once referred to the Delaware River as the "American Clyde."

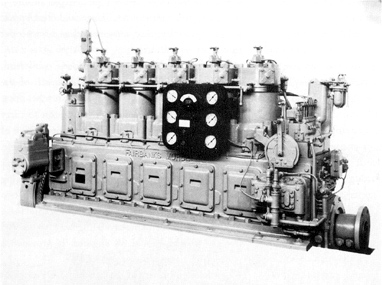

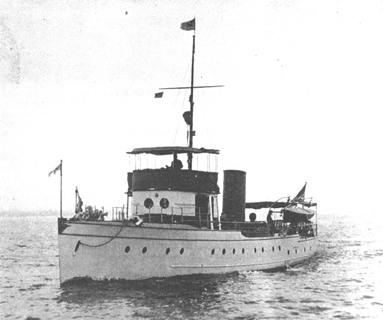

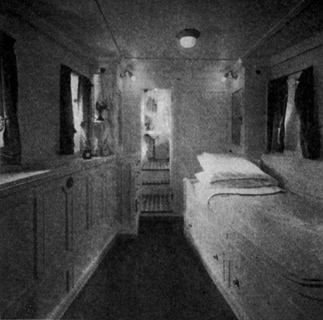

Georiana III was built for William G. Coxe, president of Harlan and Hollingsworth, and designed chiefly by the company's naval architect, A.M. Main. The vessel's overall length was 95 feet 2 ½ inches. Incorporating the "desirable and practical features of the commercial vessel, the destroyer, and the old steam yacht," the vessel marked a decided transition from traditional motor yacht construction.

In December 1916, The Motor Boat magazine reviewed the vessel and enthusiastically announced that "

Georgiana III is a real boat." Lloyd's Register of American Yachts reported the remainder of the vessel's principal dimensions as: length waterline, 93 feet; beam, 15 feet 3 inches; draft, 5 feet 6 inches; gross tonnage, 82 tons; net tonnage, 44 tons.

These dimensions indicate that

Georgiana III possessed a high length to beam ratio, the purpose of which was to increase the vessel's speed. Credited with collaborating on the vessel's design, Coxe expressly desired maximum strength and safety, with a minimum of ballast, to achieve "necessary speed, stability, comfort, etc." Her owner's desire for a substantial vessel helped usher in a new era of American power boating.

Final Voyage

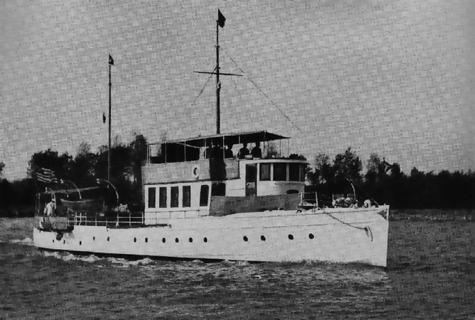

The steel yacht

Rosinco (heralded as the most palatial yacht on the Great Lakes) departed Milwaukee at about 11:30 p.m. for Chicago on September 18, 1928. At approximately 2:45 a.m the next morning (September 19, 1928), the vessel struck an underwater obstruction about 12 miles east of Kenosha. The impact tore a "deep hole" into the hull and immediately began taking on large amounts of water. All on board managed to board lifeboats just as the

Rosinco headed to the bottom. In the darkness and heavy seas, the men headed for the Kenosha lighthouse "which flashed a welcome beacon in their direction". Soon their vessel took on a leak, and all hands began bailing as they continued towards shore. After about two hours, the Kenosha Coast Guard Station spotted their distress call and met the seven men in a surfboat that then took them in tow to Kenosha. Speculation on the object that struck the

Rosinco included a pile driver (barge) that was reportedly adrift on the lake or floating dock timbers that had broken loose from a Kenosha dock that was undergoing repairs and replacement. Investigations by the Coast Guard failed to confirm either of these theories. At the time of her loss, the

Rosinco (the flagship of the Chicago Yacht Club) was valued between $100,000-$150,000.

Today

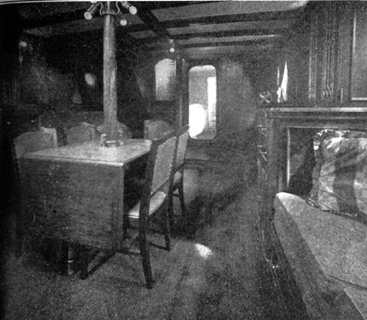

The

Rosinco is about 10 miles east of Kenosha is intact and sits upright in about 195 feet of water. The vessel is structurally intact and well preserved. Despite looting, there are still artifacts associated at the site, including silverware and china. The deck remains virtually unchanged with the windlass and collection of deck cleats, scuppers, and standing rails still remaining. Commercial fish nets drape the bow and part of the deck house.

A Federal Court case that started in 2000 by an Illinois resident claiming he had title to the

Rosinco under admiralty law, was ruled that the State of Wisconsin had title to the wreck. The benchmark case will favor archaeologists and historical preservation officials, across the country, who are trying to protect historical shipwrecks.

Confirmed Location

Confirmed Location

Unconfirmed location

Unconfirmed location