Service History

The

Daniel Lyons was launched at the height of the ship-building period in Oswego, New York. It was the first three-masted vessel built by the renowned Goble & MacFarlane Shipyard, and thus served as a model for several hundred identical vessels that followed. It cost the new owners, Daniel Lyons and George Goble, $27,000 to build. The

Daniel Lyons was a canaller built to the maximum allowable dimensions to transit the Welland Canal, and could carry 18,500 bushels of wheat through the canal locks.

The

Daniel Lyons' initial enrollment was entered on April 8, 1873, at the Port of Oswego. It was erroneously registered as having only two masts: a clerical mistake that would be repeated on all of its enrollments. Captain John Blackburn was positioned as the

Daniel Lyons' first master and commanded the vessel from its launch through the 1876 season. During this time, the

Daniel Lyons operated uneventfully as a grain trader. In 1877, Blackburn stepped down to become harbormaster of the Port of Oswego, and Captain Michael M. Holland took command of the

Daniel Lyons.

Final Voyage

As the 1878 season drew to a close, the

Daniel Lyons had nearly completed another successful year. About 1:00 a.m., Thursday, October 17, she departed Chicago with 20,000 bushels of wheat consigned to J.B. Griffin & Company of Black Rock, which is now part of Buffalo. Captain Holland was in command, assisted by First Mate Owen Madden, Second Mate Daniel Gunn, Cook W.H. Barder, and four unnamed seamen. The trip north along Wisconsin’s shoreline was unremarkable in the light westerly wind and clear skies. About 3:00 a.m. Friday morning, under a bright, waxing moon, the

Daniel Lyons passed Ahnapee, now Algoma, and the wind veered to the northwest. First Mate Madden was at the helm, and he swung the

Daniel Lyons’ bow to the northeast to accommodate the shift in wind.

Madden spotted the red and green running lights of the schooner

Kate Gillett about a mile north of the

Lyons. The

Kate Gillett was a 129-foot, two-masted schooner. It was heavily laden with fence posts from Cedar River, Michigan, and bound for Chicago.

The

Kate Gillett appeared to turn several times, but its intentions were unclear to the sailors on the

Lyons, and the two vessels drew closer to each other. After several confusing minutes, it became clear that they were about to collide. Madden swung the helm of the

Lyons in a desperate attempt to avoid the collision, but the

Kate Gillett, travelling at nine knots, struck the

Daniel Lyons’ starboard side between the main and mizzenmast, pushing its stem nearly halfway through the

Lyon’s hull. The force of the collision threw the

Daniel Lyons’ cook from his bunk. Much of the

Kate Gillett’s broken head gear crashed onto the

Daniel Lyons’ deck. Suffering damage to its starboard bow, the

Kate Gillett quickly began leaking.

It was clear the

Daniel Lyons was mortally wounded. The

Kate Gillett had cut the canaller nearly in two. The captain of the

Gillett, Jerry McCarthy, worked to keep the

Gillett’s bow lodged deep in the

Lyons to keep it from flooding until the crew could escape onto the

Gillett. The two vessels remained locked together for about 15 minutes while the

Daniel Lyons’ crew scrambled to save their possessions. Captain Holland saved some of his clothing and the ship’s books. The crew saved a portion of their belongings, the small boat, and a few lines before the two vessels separated sometime around 4:00 a.m. The

Daniel Lyons settled quickly at the stern, rolled onto its port side, and sank bow first.

Leaking badly, the

Kate Gillett continued toward Chicago. The crew of both vessels worked furiously at the pumps to keep the vessel afloat. The

Gillett safely made it to Chicago at 5:00 p.m. on Saturday, October 19, a day and a half after the collision.

The day following the accident, the schooner

Skylark encountered the wreckage of the

Lyons while enroute to Racine. Eight miles north of Ahnapee and about five miles from shore, the

Skylark’s captain reported that the

Daniel Lyons’ white topmasts were protruding from the water, still topped with gilt balls and flying the new red and blue pennant. The ship's cross trees were submerged, and the foremast had been carried away. Dispatches went out announcing the navigation hazard.

In Chicago, the

Gillett’s Captain McCarthy refused to accept responsibility for the accident and blamed Madden, the

Lyon’s helmsman. Captain Holland made no public rebuttal, but the

Lyons’ crew claimed that their vessel had had the right-of-way and the

Gillett’s captain was in error.

It is unclear whether a lawsuit was ever filed against the

Gillett, but the

Lyons’ owners would have had little incentive to do so. The

Daniel Lyons hull was valued at $15,300 and was insured by the Orient Mutual Insurance Company and Detroit Fire and Marine Company for $4,000 each. The cargo was insured by the Chicago Marine Insurance Pool for $10,500. The aging

Gillett, however, carried no insurance. A lawsuit against it could recover only the value of the

Gillett itself, which was only one-seventh that of the

Daniel Lyons and cargo.

Today

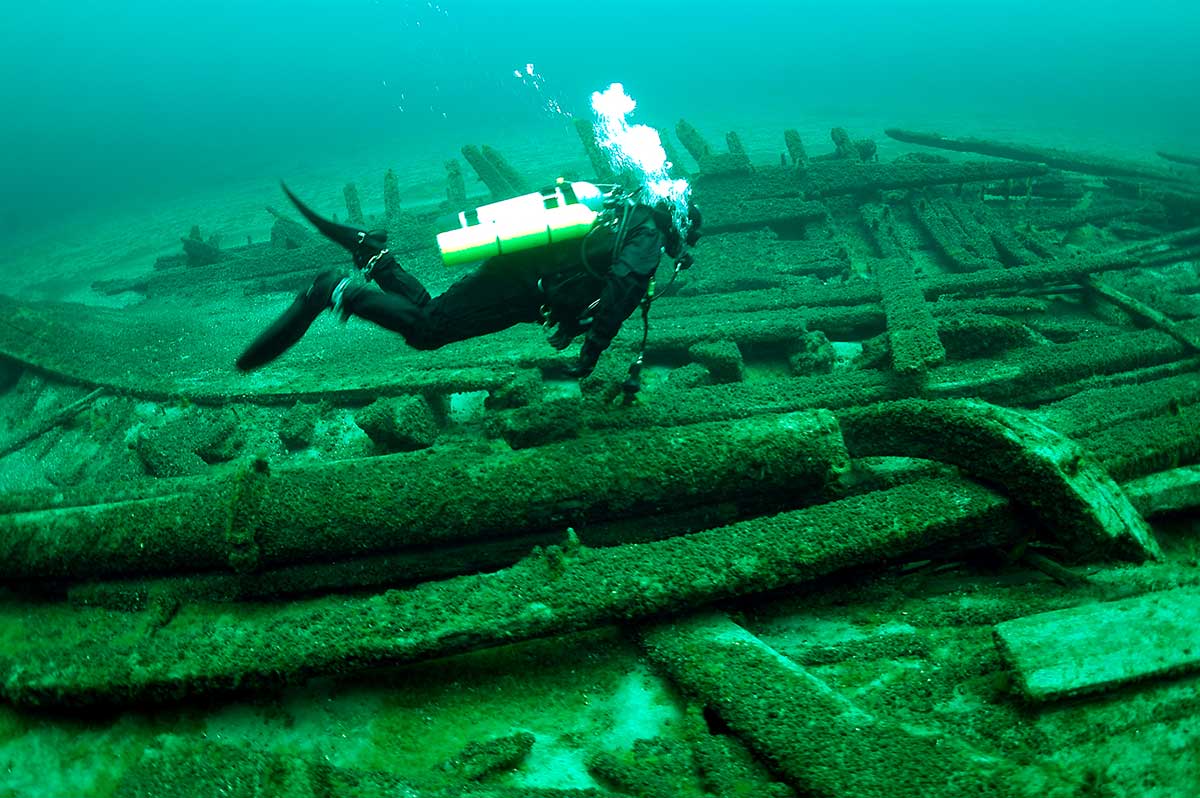

The wreck site is marked seasonally by an official state shipwreck buoy placed by the Wisconsin Historical Society. The

Daniel Lyons lies in 110 feet of water, mostly broken up, but nearly all hull structure and rigging is present and easily examined. Bottom temperatures range from 40 to 42° F, with visibility varying from 40 to 100 feet.

The

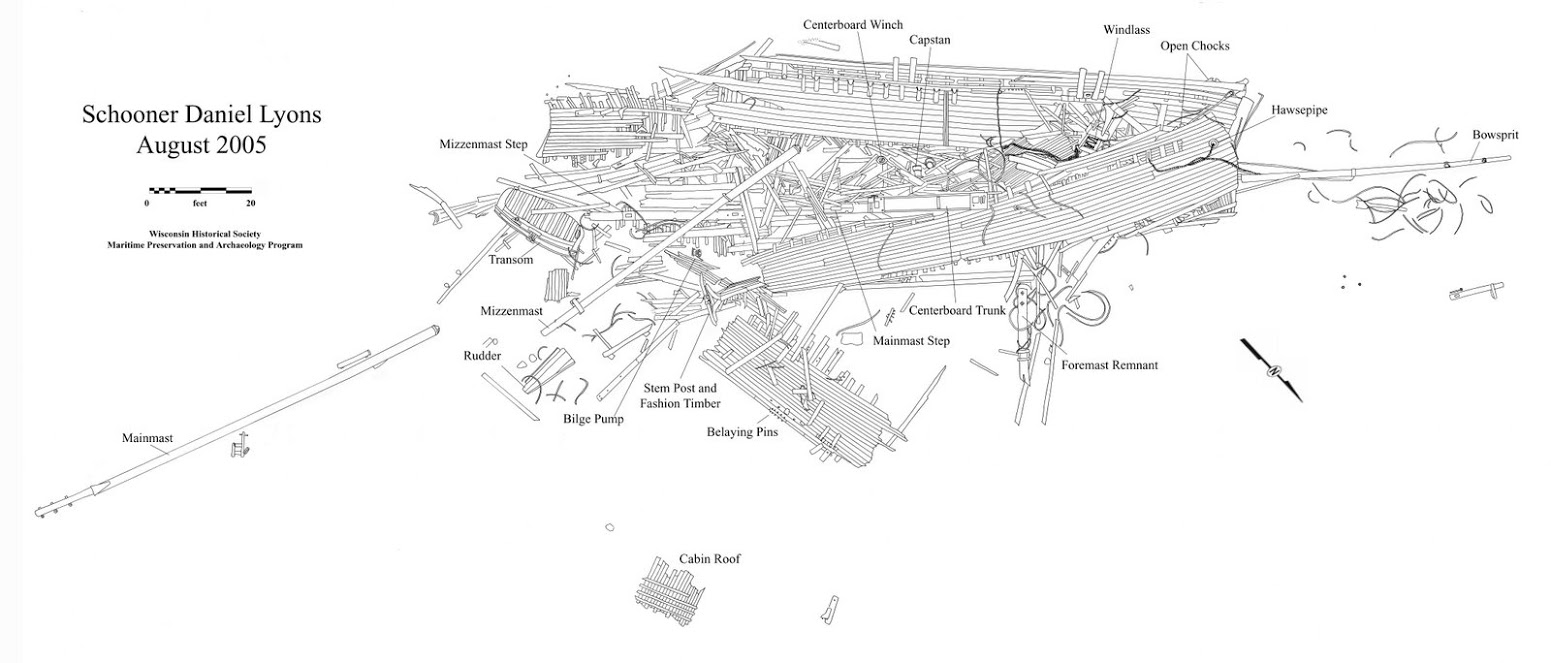

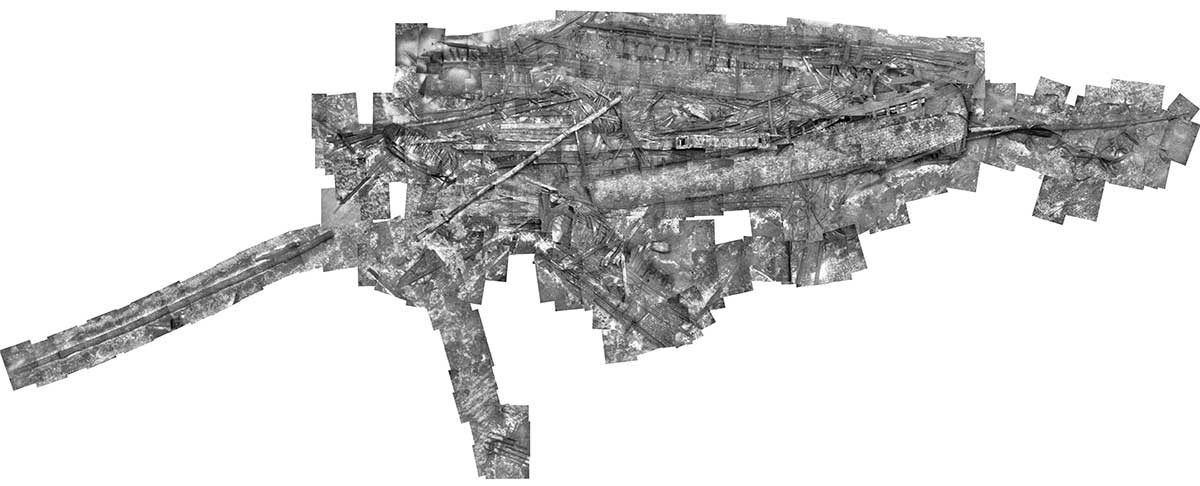

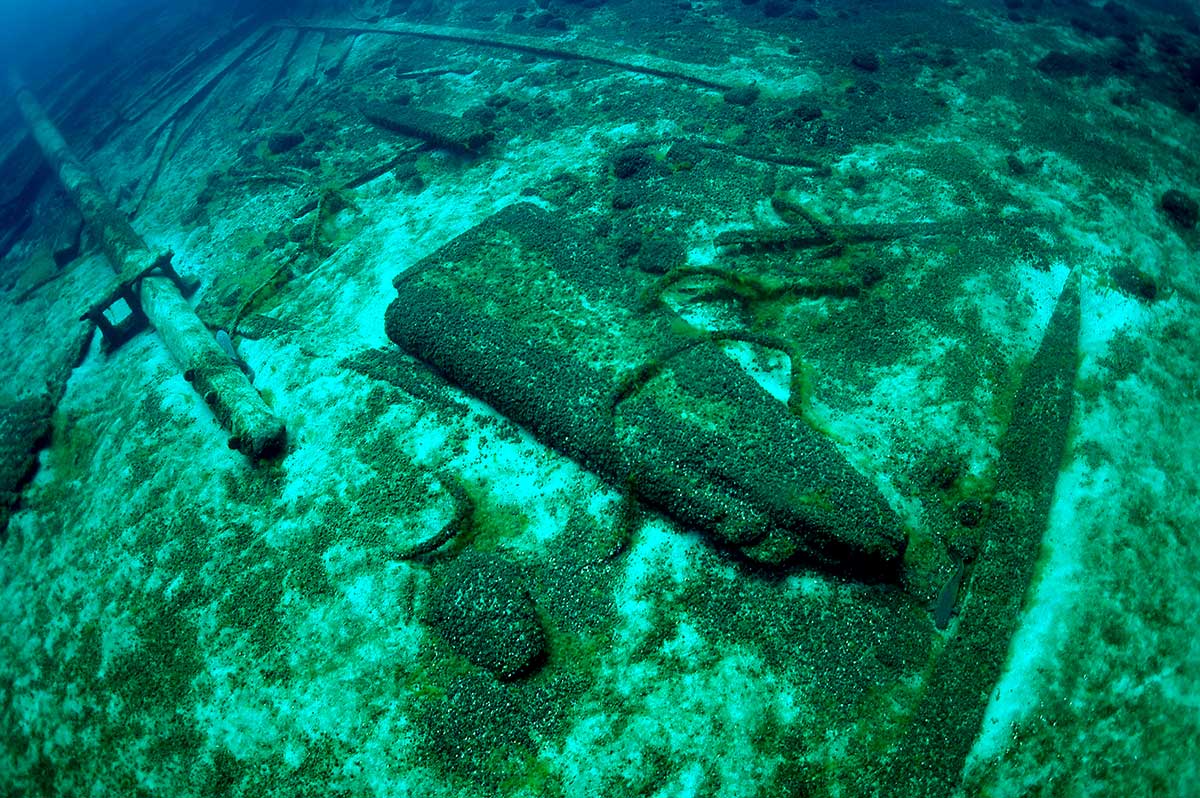

Daniel Lyons site represents a nearly complete Great Lakes schooner. The collapsed hull exposes many construction details not visible on more intact vessels. Both hull sides have collapsed to port, and the stern area is scattered off the starboard quarter. The centerboard trunk remains intact and standing, complete with the centerboard chain running from the centerboard inside the trunk to the centerboard winch lying off the trunk’s port side. Both stem and stern posts are intact with deadwood. Much of the running rigging is strewn about the wreck site, including masts, topmasts, gaffs, booms, and wire rope.

The

Daniel Lyons’ bluff bow is the site’s most visually impressive feature. Before toppling to port, the bowsprit and jib boom dislodged from their location atop the stempost and split the bow in two along the stempost’s starboard side, coming to rest atop the keelson. The bowsprit lies beneath the jib boom and extends from the starboard hull to the jib boom’s fastening ring. The bowsprit continues beneath the starboard hull, which lays somewhat flattened over the stempost, bowsprit, and windlass. A tangle of wire rigging lies around the bowsprit, as well as a sail gaff, complete with jaws, that lies immediately to starboard of the jib boom.

The port hull side has collapsed outward. It is largely intact from the transom to the bow. The centerboard trunk remains upright and visually dominates the site. The trunk is mounted atop the keelson on the vessel’s centerline. The rudder lies off the wreck site’s starboard quarter, among a tangle of wire rigging.

The

Daniel Lyons is protected by state and federal laws. The wreck is a popular site for sport divers. The

Daniel Lyons site often offers excellent conditions for taking underwater photographs and videos. To learn more about the

Daniel Lyons history and archeological findings, read the report "Wheat Chaff and Coal Dust," by Keith N. Meverden, Tamara L. Thomsen and John O. Jensen, 2006, Wisconsin Historical Society.

Confirmed Location

Confirmed Location

Unconfirmed location

Unconfirmed location