Service History

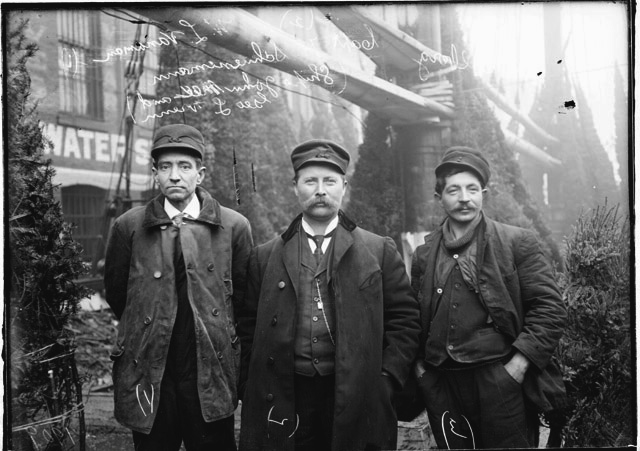

During the 19th century, Chicago was one of the busiest shipping ports in the world. A Great Lakes ship carried nearly every commodity that passed through the bustling city, Christmas trees included. Each year, several sailing ships ended their season by loading evergreens in northern Wisconsin or Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and setting sail for the Windy City. From 1890, brothers August and Herman Schuenemann, both Great Lakes sailing captains, invested in partial ownership of such vessels.

Many Christmas tree ships sold their cargo to wholesalers. Other captains, however, turned their ships into floating tree lots along the Chicago River, welcoming customers aboard and taking great pride and pleasure in their business. Each November, the captains Schuenemann loaded the schooner the

Rouse Simmons with evergreens in Thompson, Mich.

After sailing south, the pair moored their vessel to a downtown pier, hoisted a decorated tree up the mast and strung electric lights throughout the rigging, turning the ship into a large Christmas ornament. In fact, it was said that the Christmas season had not begun until the Schuenemanns arrived at their Water Street dockage. Herman Schuenemann gave away many of his trees to the city’s churches and poor, acts that earned him the name Captain Santa.

August Schuenemann was lost carrying a load of Christmas trees aboard his schooner

S. Thal just short of their home port in a late November storm in 1898. Herman’s benevolent nature was likely strengthened by his brother’s death. He didn’t take the death as prophetic but continued in the trade and in his generosity.

The Schuenemanns bought vessels late in their sailing careers, purchasing the least-expensive, aged schooners and wringing the last bit of life and profit from them in the lumber trade. Lumber was a popular cargo for aged schooners, as the lumber was not easily damaged by water in leaky vessels, and the inherent buoyancy of the cargo perhaps helped many old leaky vessels make port in a raging Lake Michigan storm. Christmas trees were also well suited for these aged lumber schooners because getting wet could not damage the trees.

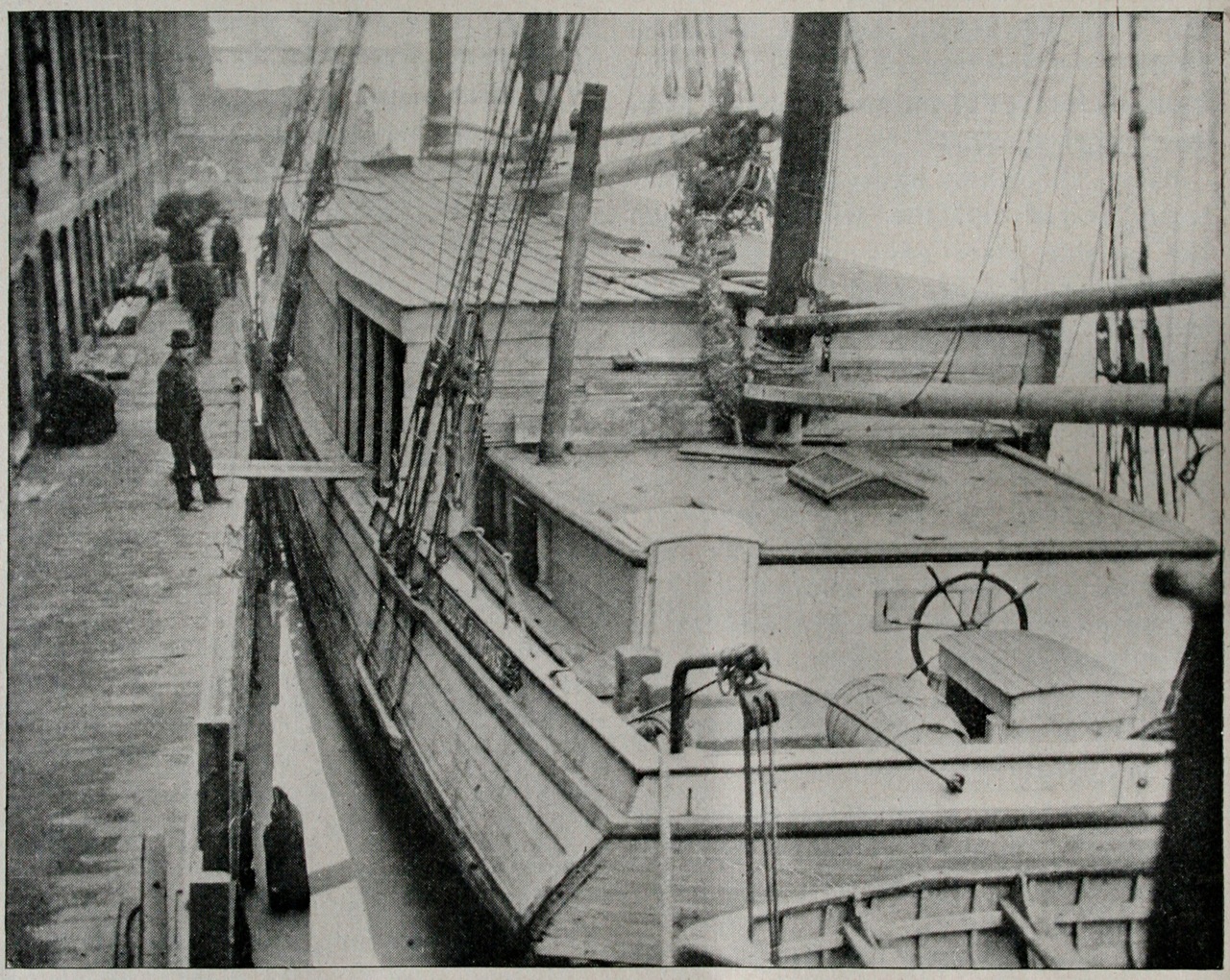

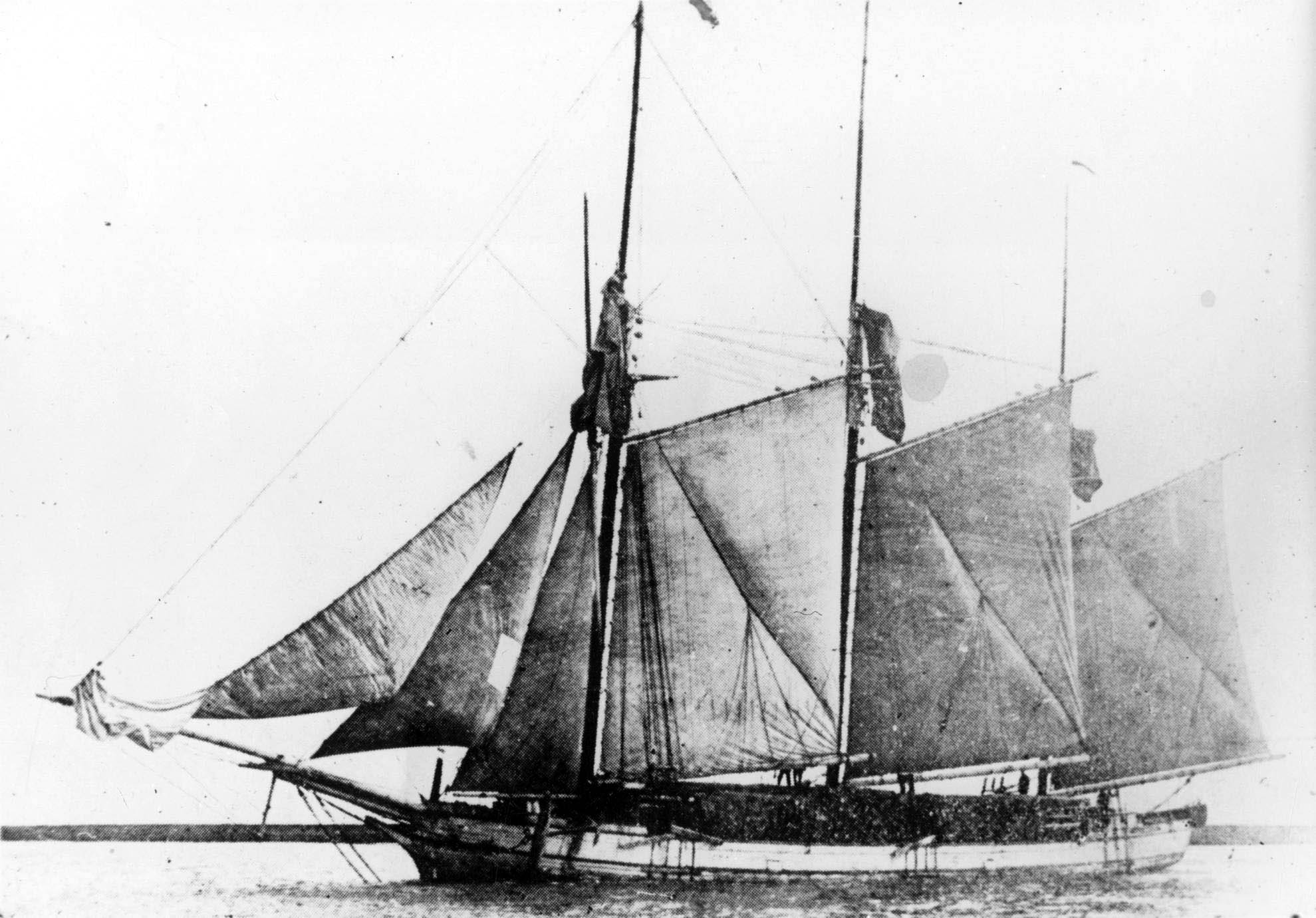

Built in 1868 by Allan McClelland and Co. in Milwaukee, the

Rouse Simmons was already 42 years old—a very old and worn boat by any standards—when Herman Schuenemann purchased his 1/8 interest. She carried three masts, and her registered dimensions were 124.2 feet in length, 27.6 feet in breadth and 10.1 feet in depth of hold. From the outside, the

Rouse Simmons was very similar to many other three-masted schooners that sailed the Great Lakes. She was markedly different from most in that she carried two centerboards rather than the more typical single centerboard of most lake sailing vessels. A vessel purposely built to serve in Lake Michigan’s lumber trade, the ship was named for the major financial backer, Rouse Simmons, whose family was a manufacturing power in Kenosha, Wis., and founder of the well-known Simmons Mattress Co.

Final Voyage

Late in the afternoon on Nov. 22, the barometer was falling and the winds were increasing as the

Rouse Simmons, fully loaded with evergreens, departed from Thompson, Mich., on her final voyage of the 1912 season. Captain Schuenemann knew the dangers of sailing in November, but there was little option for a Christmas tree merchant. Before departure, the kind-hearted Schuenemann invited a number of lumberjacks aboard to catch a ride back to Chicago to spend the holidays with friends and family. Captain Schuenemann, the

Rouse Simmons, and her estimated 16 crew and passengers never arrived at Chicago. Lost with all hands somewhere on the lake, the location of the

Rouse Simmons wreck remained a mystery for 59 years. Christmas trees washed up along the coastline for years to follow; and, in 1923, Captain Schuenemann’s wallet came up in a fisherman’s net near Two Rivers, Wis. It was not until Milwaukee diver Kent Bellrichard discovered the vessel’s remains 12 miles northeast of Two Rivers, Wis., in 165 feet of water that the story began to unfold. The discovery solved the mystery of where the

Rouse Simmons sank, but additional questions remained—why did the ship sink and what happened during her final moments?

While it will never be known for certain what transpired during the

Rouse Simmons’ final moments, an archaeological study of the wreck uncovered several clues that shed some light on what happened just before the ship slipped beneath the waves. By examining the historical and archaeological record, divers from the Wisconsin Historical Society (WHS) pieced together a more complete story of that fateful day in 1912.

Last seen by the Kewaunee Life-Saving Station, the

Rouse Simmons was flying a distress flag five miles offshore while being driven southward by a northwest gale. With no chance of catching the fleeing vessel, the Kewaunee station’s captain telephoned the Two Rivers’ Life-Saving Station, 25 miles to the south. The station immediately launched a lifeboat to intercept the distressed vessel and bring her crew to safety. When the lifeboat motored onto the lake, however, the

Rouse Simmons had vanished. In studying historic documents, it was discovered that contrary to the popular story that materialized around the

Simmons’ loss, the vessel was lost under clear conditions. She was not, as legend has it, last seen by the life-saving crew encrusted with ice, through a fleeting window in a vicious snowstorm. By recreating the search pattern of the Two Rivers lifeboat and comparing it with the

Rouse Simmons’ location today, the WHS deduced that the Two Rivers lifeboat completely encircled the

Rouse Simmons and was never more than a few miles from where she lies. With a reported six miles of visibility that day, if the ship were still afloat as the lifeboat rounded Two Rivers Point at 4:20 p.m., the life-saving crew would have seen her. Additionally, the snowstorm that many lake captains reported as “the worst they had ever seen,” may well have been terrible, but it began around 5 p.m.—well after the

Rouse Simmons would have been on the bottom.

Today

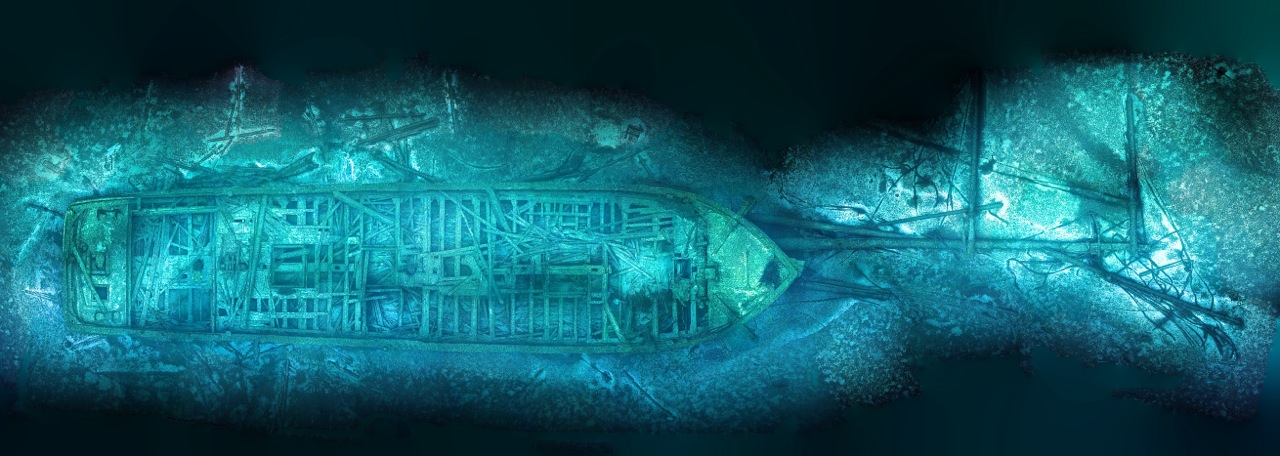

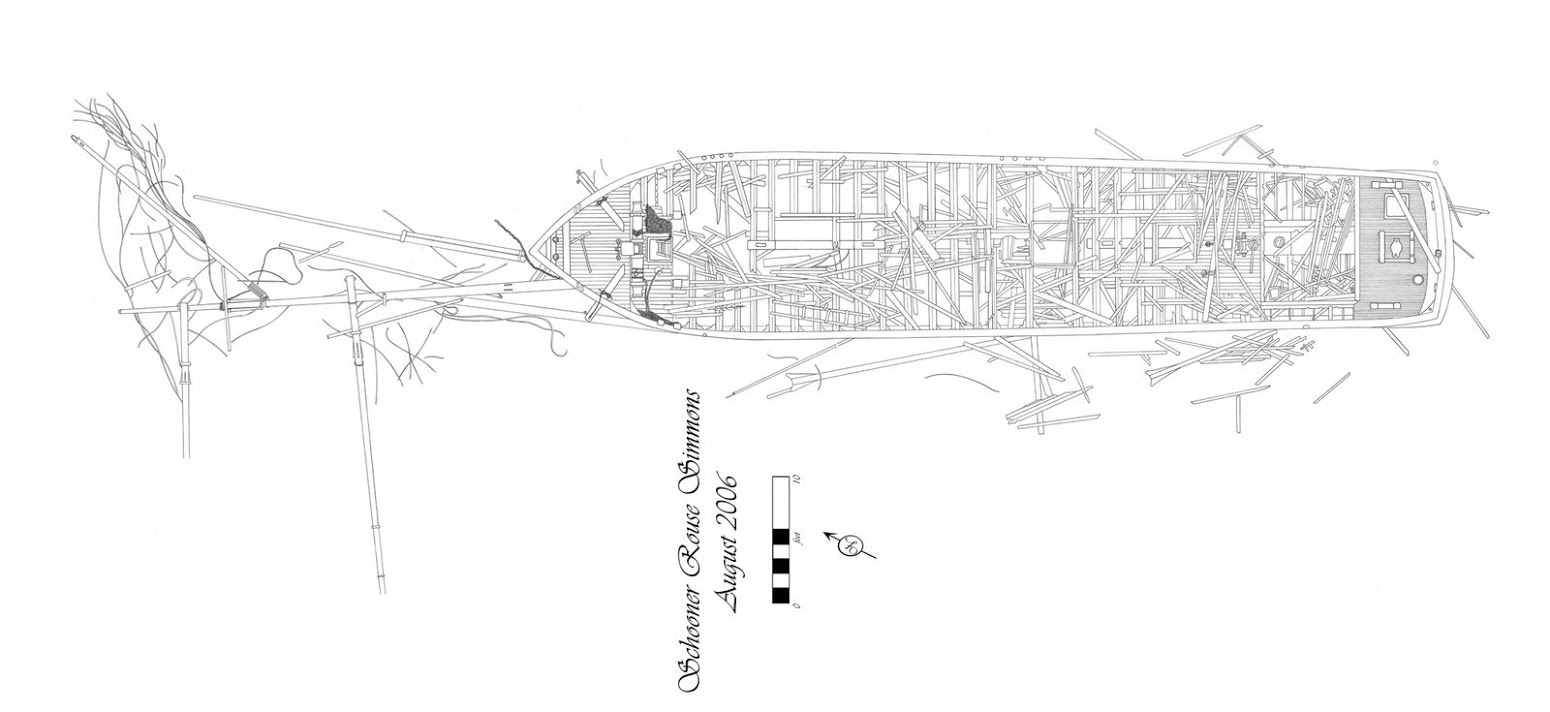

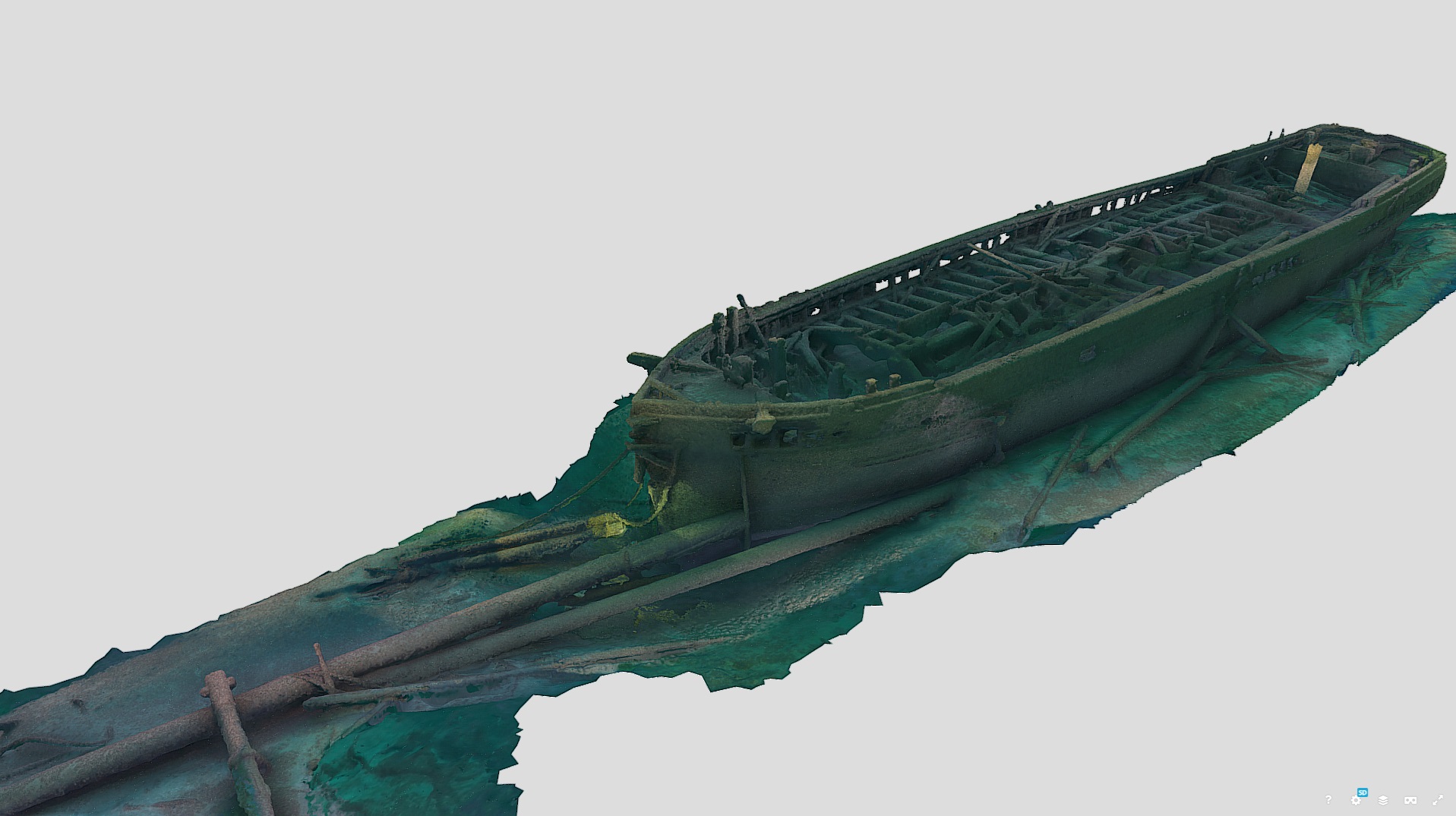

The

Rouse Simmons lies six miles northeast of Rawley Point in Manitowoc County at 44 degrees 16.640’ N, 087 degrees 24.863’ W.

The

Rouse Simmons was found facing northwest toward the shoreline, not heading south as last reported. WHS archeologists began looking for clues as to why the vessel had changed her course. With some searching, the team found tools lying about the deck on the ship’s bow. The tools were for handling the anchors and chains. The windlass was in the middle of being prepared for lowering the port side anchor; a Norman pin, an early chain stopper, was partially driven into the windlass, and the anchor chain had been removed from the chain locker and faked on deck. Using this evidence, the team initiated a search and discovered the port anchor lying 170 feet north of the bow. Given the amount of chain on the vessel, the depth of water and the intensity of the wind, it was impossible for the

Rouse Simmons to safely anchor out in the lake. Likely before the Two Rivers lifeboat rounded Two Rivers Point, something had gone seriously wrong aboard the vessel, and her crew had deployed the port anchor to hold the

Rouse Simmons into the wind. Soon after making this decision, however, large waves sent the

Rouse Simmons and her crew to the bottom of Lake Michigan.

Additionally, archeologists noticed that much of the deck planking was missing. Originally, the missing deck was attributed to anchoring damage caused by dive boats and heavy fishing of the wreck site; but upon further examination, salt channels in the deck beams (where salt was added to these early freshwater wrecks to “pickle” the wood) may have actually caused a failure in the deck fasteners—resulting in the heaved deck. It’s also likely that the estimated eight feet of trees piled high on the deck destabilized the vessel. Some reports indicated the

Rouse Simmons left Thompson, Mich., with less than a foot of freeboard under the weight of the trees. Those trees can still be found stacked neatly in the hold and, if you examine them closely, some of the trees located lower in the stacks still retain their needles.

The weight of the anchors and the chain piled on the deck contributed to the force with which the vessel struck the bottom. As the vessel hit bow first, causing a ten-foot deep divot in the sand bottom, the majority of her rigging was flung forward of the vessel where it lies on the lake bed, raking the chainplates forward, dislodging the fore and main masts and snapping the mizzen mast. Much of the hull remains intact with the exception of a few boards on her stern that were sprung as air evacuated the sinking hull.

Although the

Rouse Simmons had once been a grand ship, decades had passed since she had seen her prime—44 years of hard service on the Great Lakes. By 1912, the

Rouse Simmons was one of the last vessels still afloat from the golden age of sail, when majestic schooners with their sails raised high filled Great Lakes harbors. Great Lakes sailing vessels were nearly extinct, pushed aside by the advances of steam technology. The nostalgia surrounding the golden age of sail is the leading contributor to the perpetuation of the story of the Christmas Tree Ship. Many vessels were lost during that same storm in 1912, but the

Rouse Simmons was the Christmas Tree Ship! This schooner was something special to the people of the Chicago. The sailors and lumbermen aboard were bringing Christmas joy to the city, and they were willing to risk their lives to make Christmas merrier. This sentimentality has made the Christmas Tree Ship story everlasting and eternally shrouded in myth.

Confirmed Location

Confirmed Location

Unconfirmed location

Unconfirmed location